State transitions in aged stem cells

- 7 minsThis post is adapted from a series of posts on Twitter, so please excuse the short form nature of some descriptions.

The paper described in this post is now available (open access) at Development:

Aging induces aberrant state transition kinetics in murine muscle stem cells

Jacob C. Kimmel, Ara B. Hwang, Annarita Scaramozza, Wallace F. Marshall, Andrew S. Brack

Development 2020 : dev.183855 doi: 10.1242/dev.183855 Published 20 March 2020

Muscle stem cell activation is impaired with age

Old muscle stem cells (MuSCs) are bad at regeneration, partly because they don’t activate properly. Does aging change the set of cell states in activation, or the transition rates between them? In my final days as a graduate student, I explored this question with my excellent mentors Wallace Marshall & Andrew Brack.

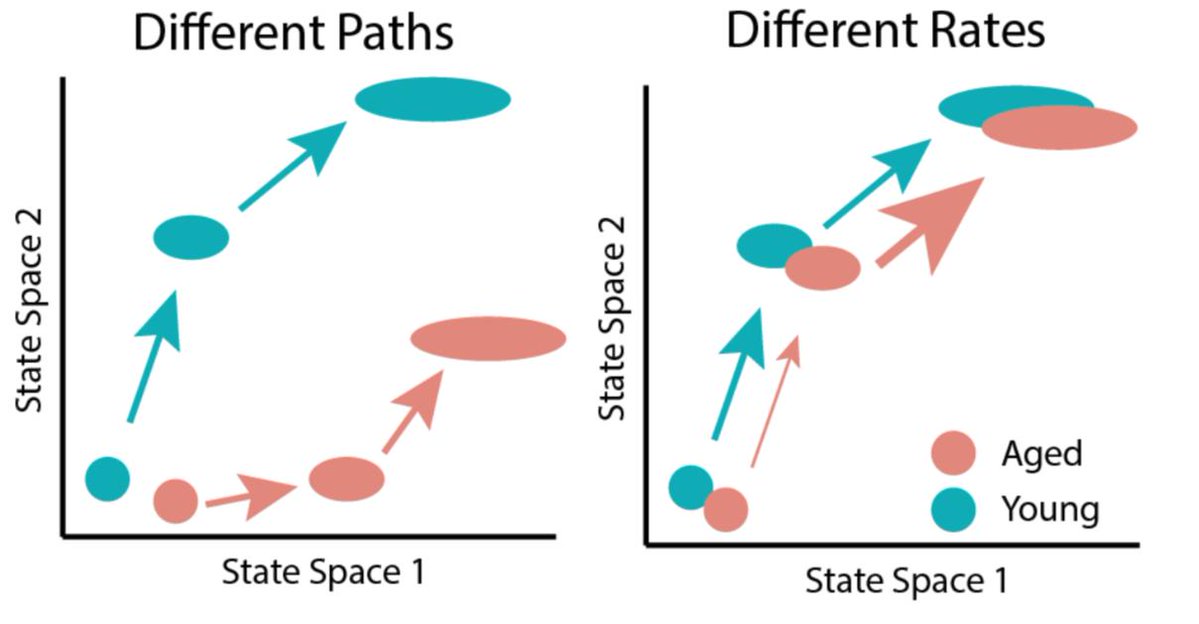

If aging changes a cellular response like stem cell activation, it might happen through two mechanisms. Aging might change the set of cell states a cell transitions through (different paths), or it might change the rate of transitions (different speeds). In biology, reality is often a weighted mixture of two models, so both of these mechanisms may be at play. How can we determine the relative contribution of each model?

Measuring the trajectory of stem cell activation in aged cells

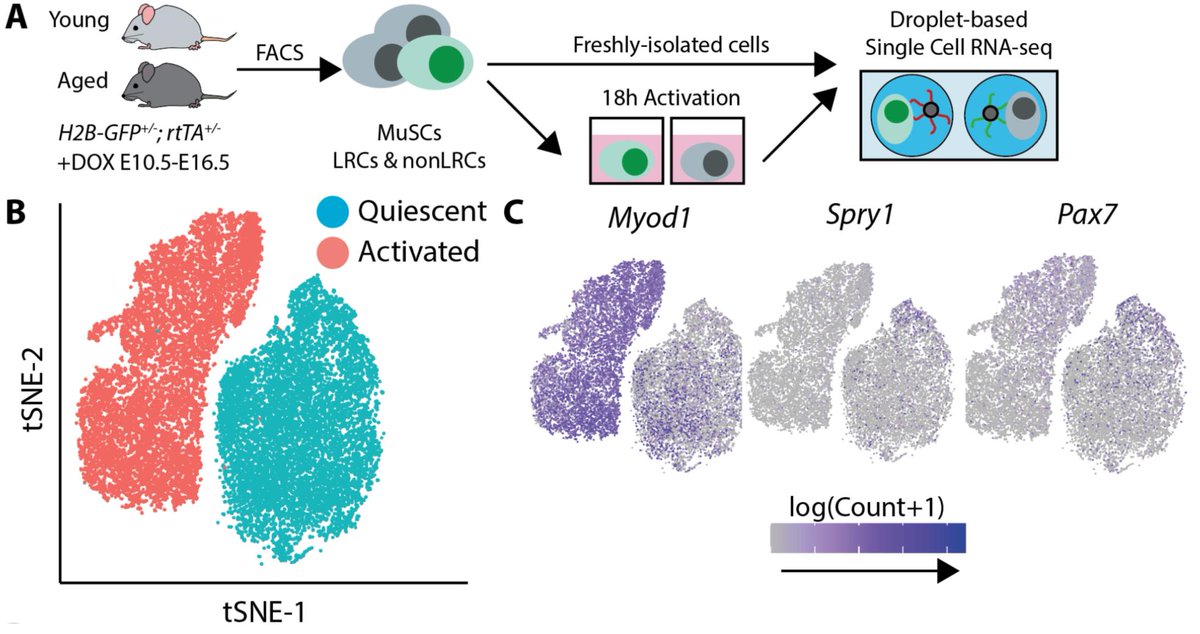

We can measure the path of activation by measuring many individual cells at a single timepoint. To estimate these paths, we measured transcriptomes of aged and young muscle stem cells with scRNA-seq during activation. As an added twist, I isolated cells from mice harboring H2B-GFP^+/-^; rtTA^+/-^ alleles that allow us to label muscle stem cells with different proliferative histories. In previous work, Andrew’s lab has shown that MuSCs which divide rarely during development (label retaining cells, LRCs) are more regenerative than those that divide a lot (non-label retaining cells, nonLRCs). By sorting these cells into separate tubes by FACS, we were able to associate each transcriptome in the single cell RNA-seq assay with both a cell age and proliferative history.

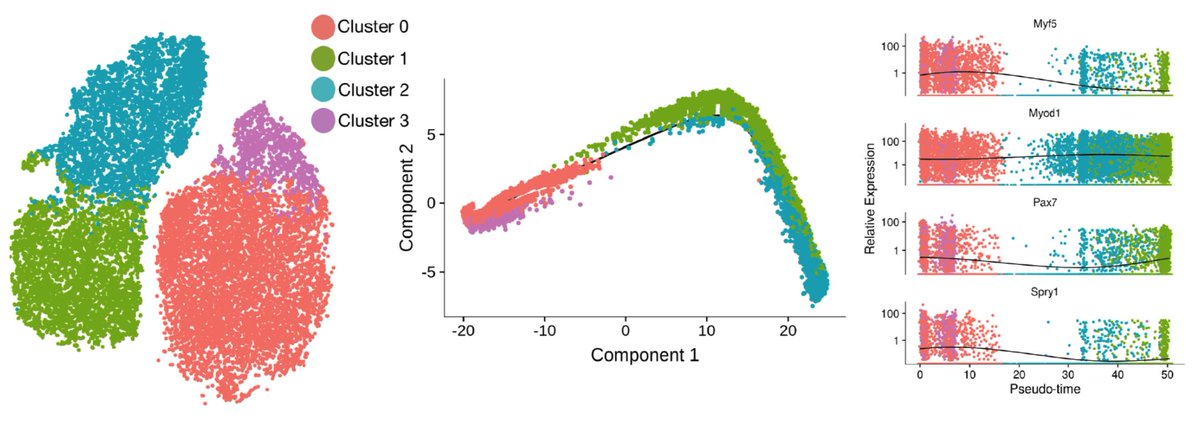

From the scRNA-seq data, we can fit a “pseudotime” trajectory to estimate the path of activation. This trajectory inference method was pioneered by Cole Trapnell, now at the University of Washington. We find this trajectory recapitulates some known myogenic biology, and also has some surprises. The one that stood out most to me was the non-monotonic behavior of Pax7. It has long been assumed that Pax7 marked the most quiescent, least activated stem cells, so it was a bit shocking to see it go back up as cells activated.

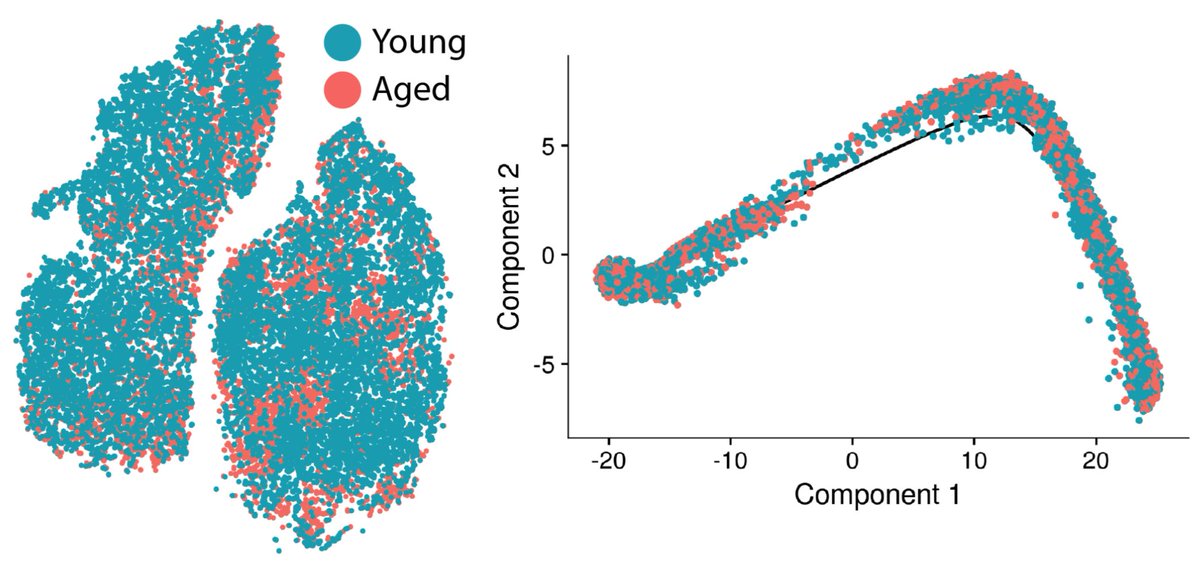

Onto the aging stuff we came for — young and aged cells are pretty evenly mixed along the same trajectory. Most aging changes are pretty subtle by differential expression, further suggesting that the change in activation trajectories with age is modest. This seems to suggest the “path” of activation is retained in aged cells.

Measuring state transitions in single cells

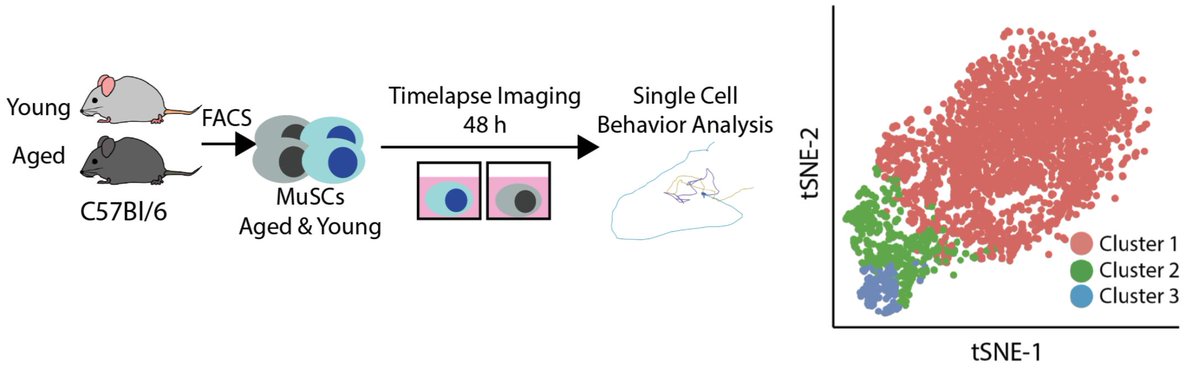

So if the paths are pretty similar across ages, are the rates different? How can we even measure state transition rates in single cells? In previous work with Wallace Marshall, I developed a tool to infer cell states from cell behavior captured by timelapse microscopy. We found we could measure state transitions during early myogenic activation in that first paper. Measuring cell state transitions rates in aged vs. young cells was an obvious next step.

So, to see if aging changes the rate of stem cell activation, we did just that. After featurizing behavior and clustering, we find that aged and young MuSCs lie along an activation trajectory, as in the first paper.

Aged and young cells again share an activation trajectory, but young cells are enriched in more activated clusters. State transition rates are higher in young cells as well. This suggests aging alters states transition rates.

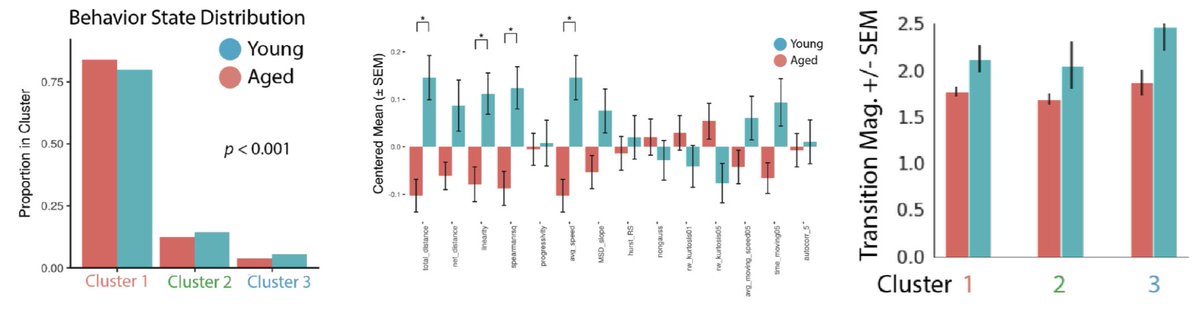

scRNA-seq and cell behavior seem to be telling a similar story. But are the states of activation they reveal the same? We investigated the non-monotonic change in Pax7 with activation that we found by single cell RNA-seq using cell behavior to find out.

We set up a cell behavior experiment, and immediately stained cells for Pax7/MyoG after the experiment was done. This allows us to map Pax7 levels to cell behavior states. We find the same non-monotonic change in Pax7 that we found by scRNA-seq!

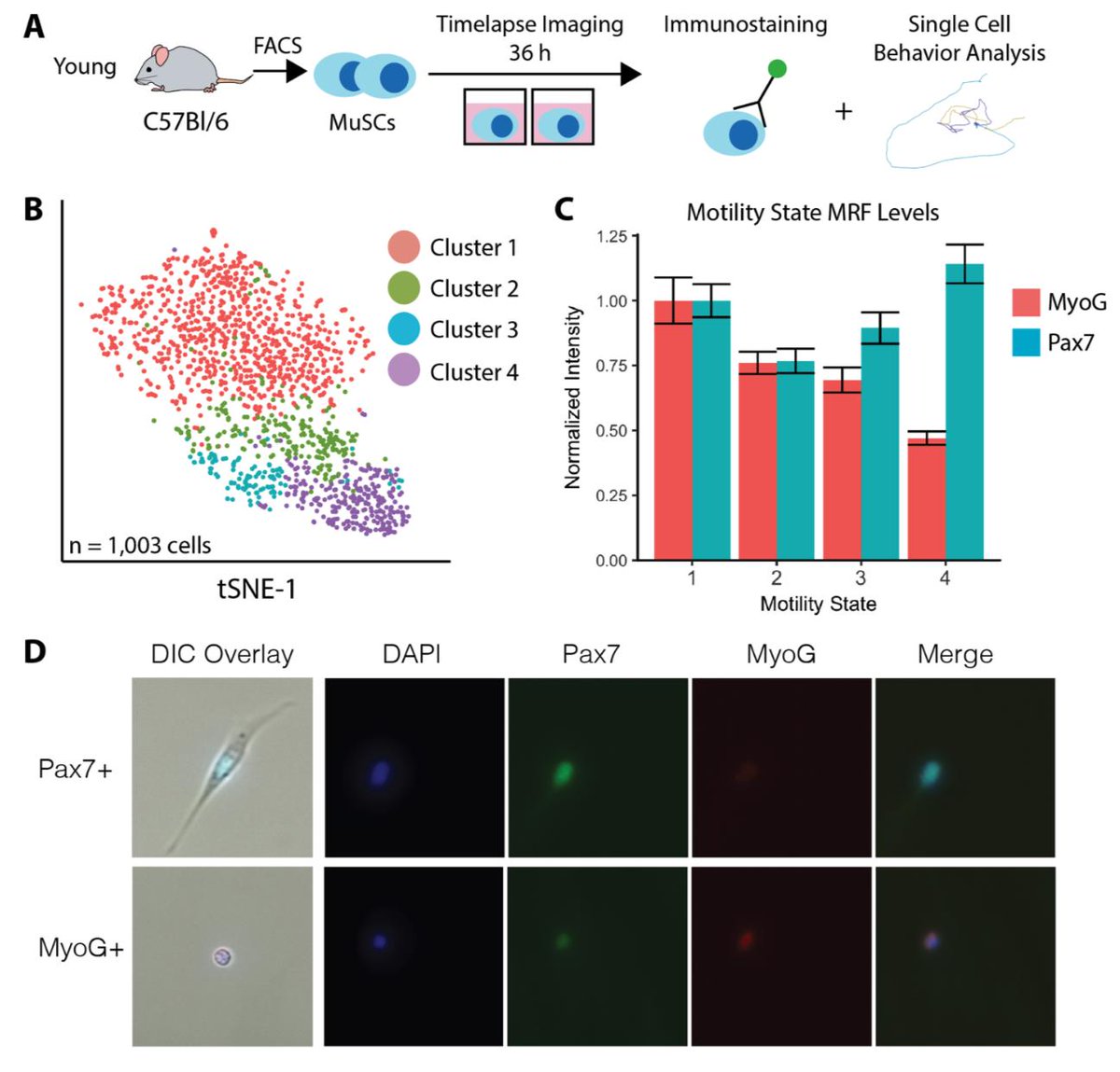

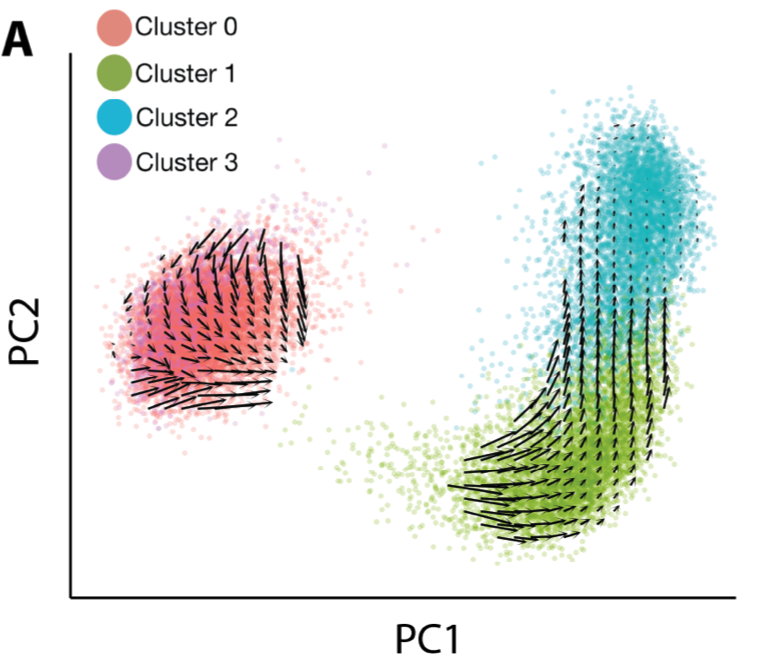

So, scRNA-seq & behavior suggest the activation trajectory is retained with age, but behavior indicates aged state transitions are slower. Can we estimate transition rates from scRNA-seq too? In brilliant work from 2018, La Manno et. al. showed that we can estimate state transitions from intronic reads in RNA-seq. We find this inference method recapitulates the activation trajectory we found with pseudotime really well.

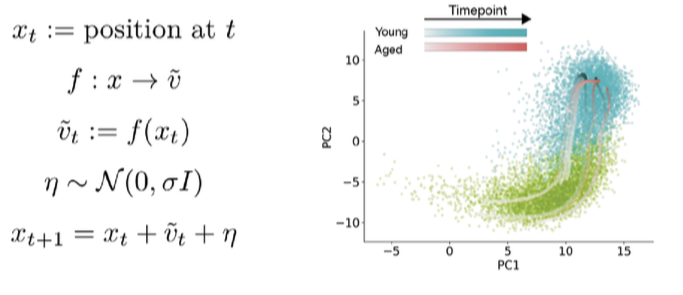

There were no obvious qualitative differences in the RNA velocity field between ages. To make quantitative comparisons though, I turned to the classic dynamical systems technique of phase simulations. A phase simulation places an imaginary point in a vector field and updates the position of the point over time based on the vectors in the neighborhood of the point.

This can reveal properties of the vector field that are hard to deduce qualitatively. Imagine floating a leaf on top of a river to figure out how fast the water is flowing. Here, I start phase points in the young/aged velocity fields, and update positions over time based on velocity of neighboring cells.

Watch an animation of this simulation process here.

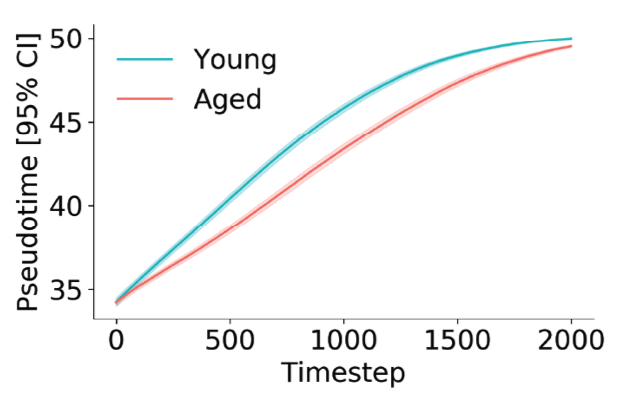

At each time step, we can infer a pseudotime of coordinate for the phase point using a simple regression model. After a thousand or so simulations, we find that young cells progress more rapidly through the activation trajectory than aged cells. This got me excited — two totally orthogonal measurement technologies telling us the same thing.

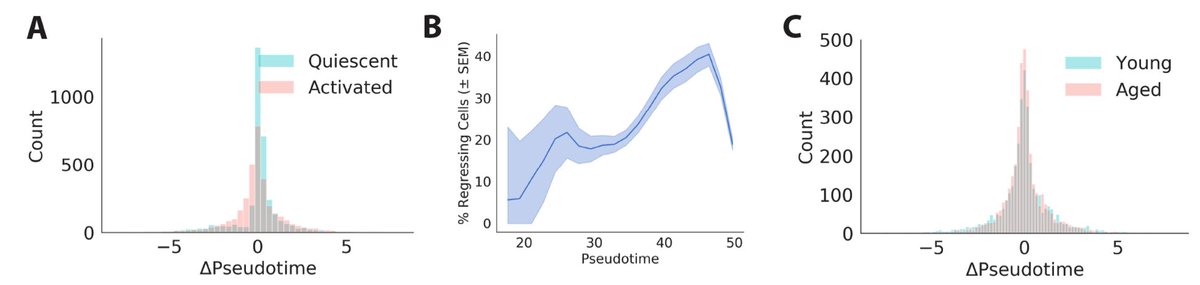

We also infer a “future” pseudotime coordinate for each cell from the velocity vector. We found many cells are moving backwards! This suggests activation is more like biased diffusion than a ball rolling downhill.

Perhaps more poetically, this reminds me of the difference between macroscopic motion and microscopic motion. In macroscopic motion, like a ball rolling down a hill, inertia takes precedence and noise is negligible. By contrast, noise often dominates the motion of microscopic particles, like a molecule of water diffusing across a glass. It seems activating muscle stem cells more closely resemble that diffusing water molecule than a ball rolling down a hill, maybe to Waddington’s chagrin.

Conclusions

In toto, both cell behavior and scRNA-seq indicate that aged MuSCs maintain youthful activation trajectories, but have dampened transition rates.