Disentangling a Latent Space

- 20 minsAn introduction to latent spaces

High-dimensional data presents many analytical challenges and eludes human intuitions. These issues area often short-handed as the “Curse of Dimensionality.” A common approach to address these issues is to find a lower dimensional representation of the high dimensional data. This general problem is known as dimensionality reduction, including common techniques like principal component analysis [PCA].

In cell biology, the high-dimensional space may consist of many measurements, like transcriptomics data where each gene is a dimension. In the case of images, each pixel may be viewed as a non-negative dimension. The goal of dimensionality reduction is then to find some smaller number of dimensions that capture biological differences at a higher layer of abstraction, such as cell type or stem cell differentiation state. This smaller set of dimensions is known as a latent space. The idea of latent space is that each latent factor represents an underlying dimension of variation between samples that explains variation in multiple dimensions of the measurement space.

Disentangled Representations

In the ideal case, a latent space would help elucidate the rules of the underlying process that generated our measurement space. For instance, an ideal latent space would explain variation in cell geometry due to cell cycle state using a single dimension. By sampling cells that vary only along this dimension, we could build an understanding of how the cell cycle effects cell geometry, and what kind of variation in our data set is explained by this singular process. This type of latent space is known as a disentangled representation. More formally, a disentangled representation maps each latent factor to a generative factor. A generative factor is simply some parameter in the process or model that generated the measurement data.

The opposite of a disentangled representation is as expected, an entangled representation. An entangled representation identifies latent factors that each map to more than one aspect of the generative process. In the cell geometry example above, an entangled latent factor may explain geometry variation due to the cell cycle, stage of filopodial motility, and environmental factors in a single dimension. This latent factor would certainly explain some variance in the data, but by convolving many aspects of the generative process together, it would be incredibly difficult to understand what aspects of cell biology were causing which aspects of this variation.

Independence is necessary, but not sufficient

Notably, independence between latent dimensions is necessary but not sufficient for a disentangled representation. If latent dimensions are not independent, they can’t represent individual aspects of a generative process in an unconfounded way. So, we need independent dimensions. However, independent dimensions are not necessarily disentangled. Two dimensions that are perfectly orthogonal could still change in unison when a particular parameter of the generative process is varied. For instance, imagine a latent space generated from cell shape images where one dimension represents the cell membrane edge shape and another represents the nuclear shape. If the cell cycle state of measured cells changes, both of these dimensions would covary with the cell cycle state, such that the representation is still “entangled.” A disentangled representation would have only a single dimension that changes covaries with the cell cycle state.

How can we find a disentangled representation?

Disentangled representations have some intuitive advantages over their entangled counterparts, as outlined by Yoshua Bengio in his seminal 2012 review. Matching a single generative factor to a single dimension allows for easy human interpretation. More abstractly, a disentangled representation may be viewed as a concise representation of the variation in data we care about most – the generative factors. A disentangled representation may also be useful for diverse downstream tasks, whereas an entangled representation may contain information to optimize the training objective that is difficult to utilize in downstream tasks 1.

However, there is no obvious route to finding a set of disentangled latent factors. Real world generative processes often have parameters with non-linear effects in the measurement space that are non-trivial to decompose. For instance, the expression of various genes over the “lifespan” of a yeast cell may not change linearly as a function of cellular age. To uncover this latent factor of age from a set of transcriptomic data of aging yeast, the latent space encoding method must be capable of disentangling these non-linear relationships.

Advances in Disentangling

I’ve been excited by a few recent papers adapting the variational autoencoder framework to generate disentangled representations. While variational autoencoders are somewhat complex, the modifications introduced to disentangle their latent spaces are remarkably simple. The general idea is that the objective function optimized by a variational autoencoder applies a penalty on the latent space encoded by a neural network to make it match a prior distribution, and that the strength and magnitude of this prior penalty can be changed to enforce less entangled representations.

Digging into the VAE Objective

To understand how and why this works, I find it helpful to start from the beginning and recall what a VAE is trying to do in the first place. The VAE operates on two types of data – $\mathbf{x}$’s in the measurement space, and $z$’s which represent points in the latent space we’re learning.

There are two main components to the network that transform between these two types of data points. The encoder $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ estimates a distribution of possible $z$ points given a data point in the measurement space. The decoder network does the opposite, and estimate a point $\mathbf{\hat x}$ in the measurement space given a point in the latent space $z$.

This function below is the objective function of a VAE2. A VAE seeks to minimize this objective by changing the parameters of the encoder $\phi$ and parameters of the decoder $\theta$.

\[{L}(\mathbf{x}; \theta, \phi) = - \mathbb{E}[ \log_{q_\phi (\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})} p_\theta (\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})] + \mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}( q_\phi (\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x}) \vert \vert p(\mathbf{z}) )\]While that looks hairy, there are basically two parts to this objective, each doing a particular task. Let’s break it down.

Reconstruction error pushes the latent space to capture meaningful variation

The first portion $-\mathbb{E}[ \log_{q_\phi (\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})} p_\theta (\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})]$ is the log likelihood of the data we observed in the measurement space $\mathbf{x}$, given the latent space $z$.

If the latent space is configured in a way that doesn’t capture much variation in our data, the decoder $p(x \vert z)$ will perform poorly and this log likelihood will be low. Vice-versa, a latent space that captures variation in $x$ will allow the decoder to reconstruct $\mathbf{\hat x}$ much better, and the log likelihood will be higher.

This is known as the reconstruction error. Since we want to minimize $L$, better reconstruction will make $L$ more negative. In practice, we estimate reconstruction error using a metric of difference between the observed data $\mathbf{x}$ and the reconstructed data $\mathbf{\hat x}$ using some metric of difference like binary cross-entropy. In order to get reasonable reconstructions, the latent space $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ has to capture variation in the measurement data. The reconstruction error therefore acts as a pressure on the encoder network to capture meaningful variation in $\mathbf{x}$ within the latent variables $\mathbf{z}$. This portion of the objective is actually very similar to a “normal” autoencoder, simply optimizing how close we can make the reconstructed $\mathbf{\hat x}$ to the original $\mathbf{x}$ after forcing it through a smaller number of dimensions $\mathbf{z}$.

Divergence from a prior distribution enforces certain properties on the latent space

The second part of the objective

\[\mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}( q (\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x}) \vert \vert p(\mathbf{z}) )\]measures how different the learned latent distribution $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ is from a prior we have on the latent distribution $p(\mathbf{z})$. This difference is measured with the Kullback-Leibler divergence 3, which is shorthanded \(\mathbb{D}_\text{KL}\). The more similar the two are, the lower the value of $\mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}$ and the therefore the lower the value of the loss $L$. This portion of the loss therefore “pulls” our encoded latent distribution to match some expectations we set in the prior. By selecting a prior $p(\mathbf{z})$, we can therefore enforce some features we want our latent distribution $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ to have.

This prior distribution is often set to an isotropic Gaussian with zero mean \(\mu = 0\) and a diagonalized covariance matrix with unit scale $\Sigma = \mathbf{I}$, where $\textbf{I}$ is the identity matrix, so $p(\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(0, \textbf{I})$ 4. Because the prior has a diagonal covariance, this prior pulls the encoded latent space $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ to have independent components.

Reviewing the Objective

Taking these two parts together, we see that the objective part 1 optimizes $p(\mathbf{x} \vert \mathbf{z})$ and $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ to recover as much information as possible about $\mathbf{x}$ after encoding to a smaller number of latent dimensions $\mathbf{z}$ and 2 enforces some properties we desire onto the latent space $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ based on a desiderata we express in a prior distribution $p(\mathbf{z})$.

Notice that the objective doesn’t scale either of the reconstruction or divergence loss in any way. Both are effectively multiplied by a coefficient of $1$ and simply summed to generate the objective.

What sort of latent spaces does this generate?

The Gaussian prior $p(\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})$ pulls the dimensions of the latent space to be independent.

Why? The covariance matrix we specified for the prior is the identity matrix $\mathbf{I}$, where no dimension covaries with any others. However, it does not explicitly force the disentangling between generative factors that we so desire. As we outlined earlier, independence is necessary but not sufficient for disentanglement. The latent spaces generated with this unweighted Gaussian prior often map multiple generative factors to each of the latent dimensions, making them hard to interpret semantically.

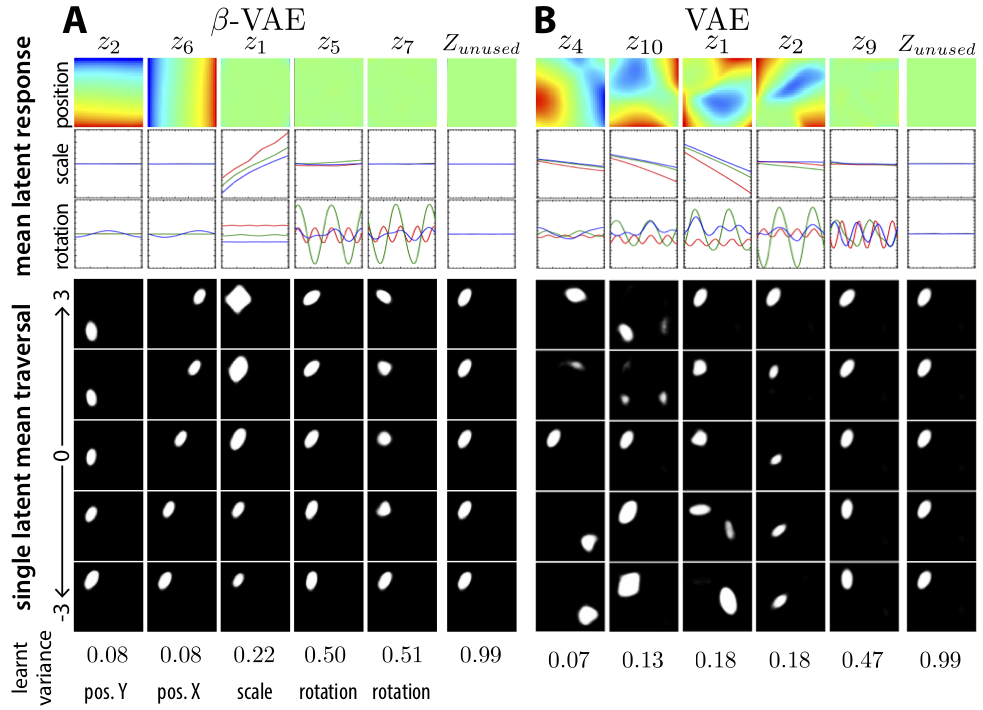

We can see an example of this entangling between generative factors in a VAE trained on the dSprites data set. dSprites is a set of synthetic images of white objects moving across black backgrounds. Because the images are synthesized, we have a ground truth set of generative factors – object $x$ coordinate, object $y$ coordinate, shape, size, rotation – and we know the value of each generative factor for each image.

Borrowed from Higgins 2017 Figure 7, here’s a visualization of the latent space learned for dSprites with a standard VAE on the right side. Each column in the figure represents a latent space traversal – basically, latent vectors $\mathbf{z}$ are sampled with all but one dimension of $\mathbf{z}$ fixed, and the remaining dimension varied over a range. These vectors are then decoded using the trained VAE decoder. This lets us see what information is stored in each dimension.

If we look through each latent dimension for the standard VAE on the right side, we see that different generative factors are all mixed together in the model’s latent dimensions. The first dimension is some mixture of positions, shapes and scales. Likewise for the second and third columns. As a human, it’s pretty difficult to interpret what a higher value for dimension number $2$ in this model really means.

Curious readers will note that the columns on the left side of this figure seem to map much more directly to individual parameters we can interpret. The first one is the $Y$ position, the second is $X$ position, &c.

How can we encourage our models to learn representations more like this one on the left?

Modifying the VAE Objective

Trying to encourage disentangled representations in VAEs is now a very active field of research, with many groups proposing related ideas. One common theme explored by several methods to encourage disentanglement is the modification of the VAE objective, reviewed wonderfully by Tschannen et.al.. How might we modify the objective to encourage this elusive disentanglement property?

$\beta$-VAE: Obey your priors young latent space

One strategy explored by Higgins et. al. and Burgess et. al. at DeepMind is to simply weight the KL term of the VAE objective more heavily. Recall that the KL term in the VAE objective encourages the latent distribution $q(z \vert x)$ to be similar to $p(z)$. If $p(z) = \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})$, this puts more emphasis on matching the independence between dimensions implied by the prior.

The objective Higgins et. al. propose is a beautifully simple modification to the VAE objective.

We go from:

\[{L}(x; \theta, \phi) = - \mathbb{E}[ \log_{q_\phi (z \vert x)} p_\theta (x \vert z)] + \mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}( q_\phi (z \vert x) \vert \vert p(z) )\]to:

\[{L}(x; \theta, \phi) = - \mathbb{E}[ \log_{q_\phi (z \vert x)} p_\theta (x \vert z)] + \beta \mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}( q_\phi (z \vert x) \vert \vert p(z) )\]Notice the difference? We added a $\beta$ coefficient in front of the KL term. Higgins et. al. set this term $\beta > 1$ to encourage disentanglement and term their approach $\beta$-VAE.

As simple as this modification is, the results are quite striking. If we revisit the dSprites data set above, we note that simply weighting the KL with $\beta = 4$ leads to dramatically more interpretable latent dimensions than $\beta = 1$. I found this result quite shocking – hyperparameters in the objective really, really matter!

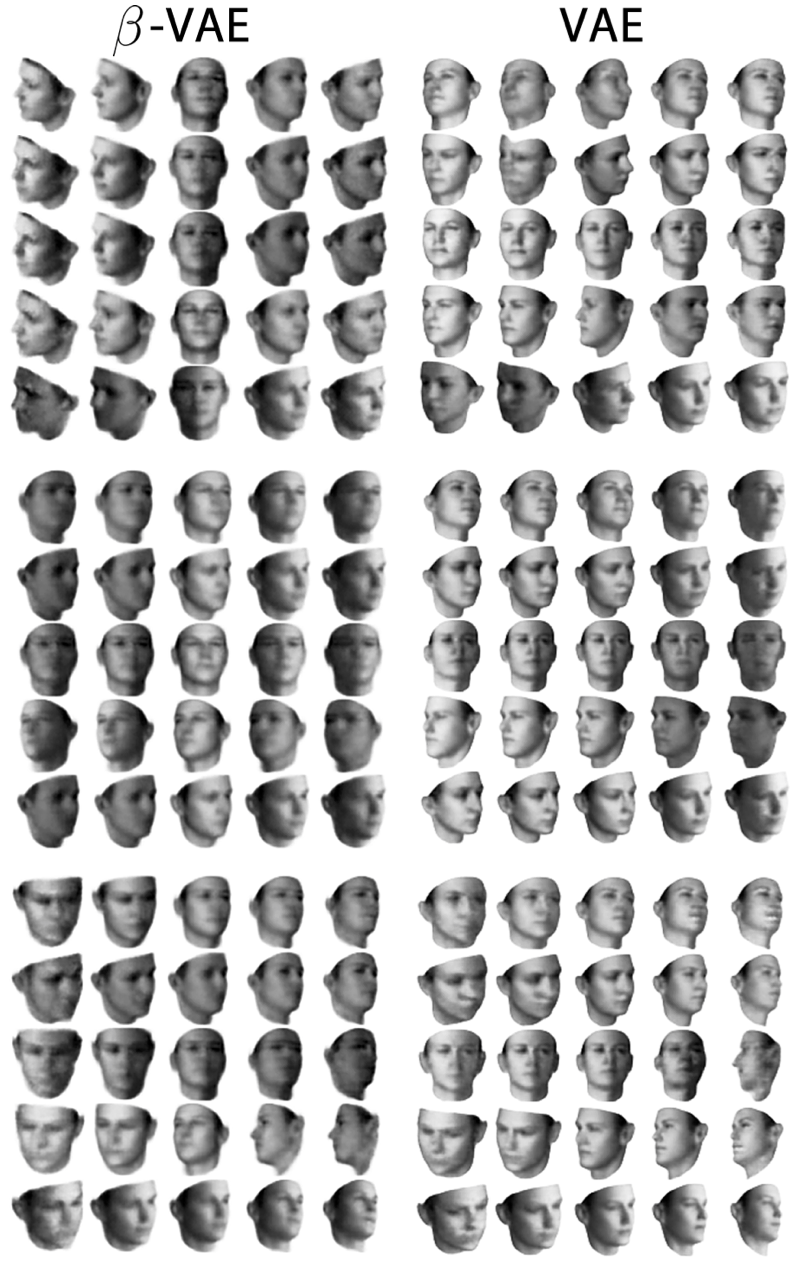

Here’s another example from Higgins 2017 using a human face dataset. We see that $\beta$-VAE learns latent dimensions that specifically represent generative factors like azimuth or lighting condition, while a standard VAE objective $\beta = 1$ tends to mix generative factors together in each latent dimension.

Why does this work?

In a follow up paper, Burgess et. al. investigate why this seems to work so well. They propose that we view $q(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{x})$ as an information bottleneck. The basic idea here is that we want $\mathbf{z}$ to contain as much information as possible to improve performance on a task like reconstructing the input, while discarding any information in $\mathbf{x}$ that isn’t necessary to do well on the task.

If we take a look back at the VAE objective, we can convince ourselves that the KL divergence between the encoder $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ and the prior $p(\mathbf{z})$ is actually an upper bound on how much information about $\mathbf{x}$ can pass through to $\mathbf{z}$ 5. This “amount of information” is referred to in information theory as a channel capacity.

By increasing the cost of a high KL divergence, $\beta$-VAE reduces the amount of information that can pass through this bottleneck. Given this constraint, Burgess et. al. propose that the flexible encoder $q(\mathbf{z} \vert \mathbf{x})$ learns to map generative factors to individual latent dimensions as an efficient way to encode information about $\mathbf{x}$ necessary for reconstruction during decoding.

While somewhat intuitive-feeling, there isn’t much quantitative data backing this argument. The exact answer to why simply weighting the KL a bit more in the VAE objective gives such remarkable results is still, alas, an open question.

Based on this principle, Burgess et. al. also propose letting more information pass through the bottleneck over the course of training. The rationale here is that we can first use a small information bottleneck to learn a disentangled but incomplete representation. After latent dimensions have associated with generative factors, we can allow more information into the bottleneck to improve performance on downstream tasks, like reconstruction or classification, while maintaining this disentanglement.

To do this, the authors suggest another elegant modification to the objective:

\[{L}(x; \theta, \phi) = - \mathbb{E}[ \log_{q_\phi (z \vert x)} p_\theta (x \vert z)] + \beta \vert \mathbb{D}_{\text{KL}}( q_\phi (z \vert x) \vert \vert p(z) ) - C \vert\]where $C$ is a constant value that increases over the course of VAE training. As $C$ increases, we allow the KL divergence term to increase correspondingly without adding to the loss. The authors don’t provide direct comparisons between this new modification and $\beta$-VAE alone though, so it’s hard to know how much benefit this method provides.

How do we measure disentanglement?

You may have noticed that previous figures rely on qualitative evaluation of disentanglement. Mostly, we’ve decoded latent vectors along each dimension and eye-balled the outputs to figure out if they map to a generative factor. This kind of eye-balling makes for compelling figures, but it’s hard to rigorously compare “how disentangled” two latent spaces are using just this scheme.

Multiple quantitative metrics have also been proposed 6, but they can only be used in synthetic data sets where the generative factors are known – like dSprites, where we simulate images and know what parameters are used to generate each image. Developing methods to measure disentanglement in a quantitative manner seems like an important research direction going forward.

In the case of biological data, we might imagine evaluating disentanglement on generative factors we know, like experimental conditions. Imagine we’ve captured images of cells treated with different doses of a drug. If the different doses of the drug mapped to a single dimension of the latent space, we may consider that representation to be more disentangled than a representation where drug dose is explained across many dimensions.

Much of the promise in learning disentangled representations is in the potential for discovery of unknown generative factors. In an imaging experiment like the one above, perhaps cell motility states map to a dimension – moving, just moved, not moving – even if we didn’t know how to measure those states explicitly beforehand. Evaluating representations for their ability to disentangle these unknown generative factors seems like a difficult epistemic problem. How do we evaluate the representation of something we don’t know to measure? Research in this area may have to rely on qualitative evaluation of latent dimensions for the near future. In some cases, biological priors may help us in evaluating disentanglement, as shown by work in Casey Greene’s group using gene set enrichment to evaluate representations 7.

Where shall we venture?

I’d love to see how these recent advances in representation learning translate to biological problems, where it’s sometimes difficult to even know if a representation is disentangled. This seems intuitively the most useful to me in domains where our prior biological knowledge isn’t well structured. In some domains like genomics, we have well structured ontologies and strong biological priors for associated gene sets derived from sequence information and decades of empirical observation. Perhaps in that domain, explicit enforcement of those strong priors will lead to more useful representations 8 than a VAE may be able to learn, even when encouraged to disentangled.

Cell imaging on the other hand has no such structured ontology of priors. We don’t have organized expressions for the type of morphologies we expect to associate, the different types of cell geometry features are only vaguely defined, and the causal links between them even less so. Whereas we understand that transcription factors have target genes, it remains unclear if nuclear geometry directly influences the mitochondrial network. Imaging and other biological domains where we have less structured prior knowledge may therefore be the lowest hanging fruit for these representation learning schemes in biology.

Footnotes

-

For instance, information used to improve reconstructions in a VAE may not be useful for clustering the data in the latent space. This last point is notably hard to prove, as the specific representation that is best for any given task will depend on the task. See Tschannen et.al. for a formal treatment of this topic.. ↩

-

An Objective function is also known as a loss function or energy criterion. ↩

-

The Kullback-Leibler divergence is a fundamental concept that allows us to measure a distance between two probability distributions. Since “the KL” is a divergence (something like a distance, but it doesn’t obey the triangle inequality), it is bounded on the low end at zero and unbounded on the upper end. \(\mathbb{D}_\text{KL} \rightarrow [0, \infty)\). ↩

-

The identity matrix $\mathbf{I}$ is a square matrix with $1$ on the diagonal and $0$ everywhere else. In mathematical notation, $\mathcal{N}(\mu, \Sigma)$ is used to shorthand the Gaussian distribution function. ↩

-

We can think of $\mathbf{z}$ as a “channel” through which information about $\mathbf{x}$ can flow to perform downstream tasks, like decoding and reconstructing of $\mathbf{x}$ in an autoencoder.

If we think about how to minimize the KL, we realize that the KL will actually be minimized when $q(z_i \vert x_i) = p(\mathbf{z})$ for every single example. This is true if we recall that the KL is $0$ when the two distributions it compares are equal.

If we set out prior to $p(\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{I})$ as above, this means that the KL would be minimized when $q(z_i | x_i) = \mathcal{N}(\mu_i = \mathbf{0}, \sigma_i = \mathbf{I})$ for every sample. If the values are the same, they obviously contain no information about the input $\mathbf{x}$!

So, we can think of the value of the KL as a limit on how much information about $\mathbf{x}$ can pass through $\mathbf{z}$, since minimizing the KL forces us to pass no information about $\mathbf{x}$ in $\mathbf{z}$. ↩

-

See Higgins et. al. 2017 and Kim et. al. 2018. ↩

-

See Taroni 2018, Way 2017, Way 2019 ↩